Agility is on everyone’s lips—online searches for “agile transformation” yield around 100 million hits, and the stories of well-known pioneers circulate widely. But is this just hype, or are there real benefits to be gained? Is agility just noise from the IT department, or an opportunity that merits serious attention from the top team? And if pursuing agility yields benefits, what is the recipe for success?

To find the answers, we conducted a McKinsey Global Survey that reached 2,190 respondents across industries and geographies.1 We wanted to go beyond the fluff, so we asked respondents what, if anything, their companies did in practice to advance agility, and what hard numbers they achieved regarding business impact.

Their organizations fell into two broad groups: the first group consisted of organizations with no agile transformation efforts in process; the second group consisted of organizations on the move, pursuing, or having recently completed an agile transformation beyond a few individual teams (see sidebar “Organizations are on the move”). Two-thirds of those pursuing a transformation, however, said that their organizations were just treading water, taking no decisive action, and consequently achieving little or no business impact.

Within this second group, we identified a select set of organizations (represented by 10 percent of the entire sample) that were driving highly successful agile transformations. They were embracing agility at scale to create and capture value instead of treating agile as team-level experiments in discrete departments. This means reimagining the entire organization as a network of high-performing teams, each going after clear, end-to-end business-oriented outcomes, and possessing all of the skills needed to deliver, such as a bank boosting the performance of customer journeys; a retailer analyzing turns and earns of product categories; a mining company reviewing production- and safety-process steps; an oil and gas company planning wells; a machinery player undertaking full product management, from R&D to go-to-market; or a teleoperator simplifying products. The teams are essentially interconnected mini businesses, obsessed with creating value rather than just delivering functional tasks.

However, agility at scale goes beyond adding more agile teams and team-level practices. The broader operating model, the connective tissue between and across the teams, also needs to be transformed. The organizations driving highly successful agile transformations made sure to do that by building an effective, stable backbone. This means optimizing the full operating model across strategy, structures, processes, people, and technology by going after flat and fluid structures built around high-performing cross-functional teams, instituting more frequent prioritization and resource-allocation processes, building a culture that enables psychological safety, and decoupling technology stacks.

Enterprise agility is thus a paradigm shift away from multilayered reporting structures, rigid annual budgeting, compliance-oriented culture, separation of business and technology, and other traits dominating organizations for the past hundred years. If this is true, and not just hype, a discontinuity of this magnitude should provide an opportunity for organizations to turn their operating models into a competitive advantage—as did early adopters of lean in the 1990s.

While individual case studies and agile success stories have been plentiful, having quantifiable results and a larger sample allowed us to go beyond anecdotes for the first time. Two major findings emerged.

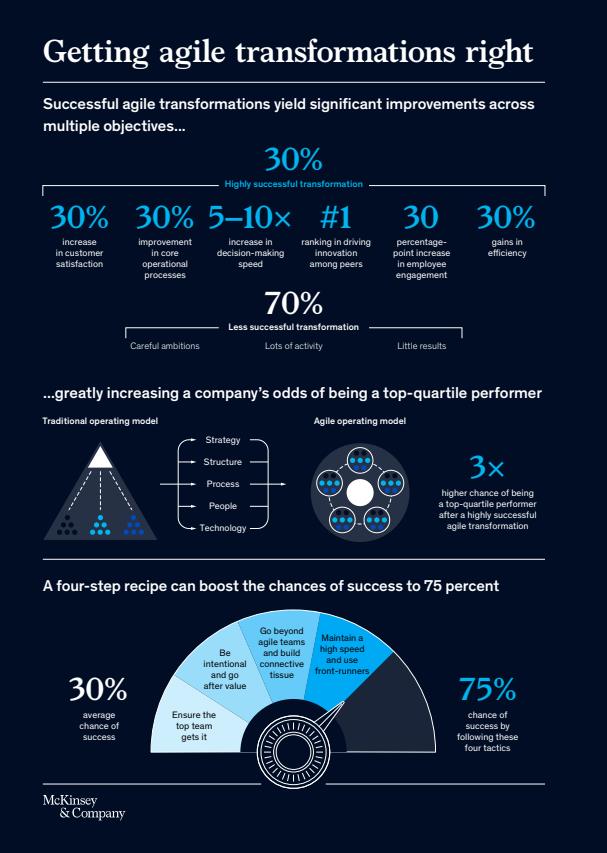

1. Agility results in a step change in performance and makes it possible to overtake born-agile organizations. Highly successful agile transformations typically delivered around 30 percent gains in efficiency, customer satisfaction, employee engagement, and operational performance; made the organization five to ten times faster; and turbocharged innovation. While conventional wisdom sometimes sees these targets as contradictory (for example, efficiency at the cost of employee engagement), our results show otherwise. The respondents, on average, reported gains across four dimensions of performance, out of seven included in the survey.

This step change also showed up as a competitive advantage. Organizations that achieved a highly successful agile transformation had a three times higher chance of becoming a top-quartile performer among peers than those who had not transformed. And they also overtook the born-agile organizations: they not only had a higher chance of becoming a top-quartile performer, but also had a greater chance of achieving a more mature operating model across all dimensions.

2. Instead of waiting for agility to happen bottom-up, organization leaders need to take charge. Our survey asked respondents in detail what actions they took before and during their agile transformations. Our analysis then compared the close to 300 highly successful transformations with the 580 less successful ones to distill what they did differently. Four elements stood out in our logistic regression model, and together these formed a recipe that raises the chance of success from an average of 30 percent to 75 percent:

- Ensure the top team gets it. Before you start, spend sufficient time up front to ensure the top team masters the concepts and can lead the change.

- Be intentional and go after value. Be clear on how agile creates value and have the top team lead the organization to pursue it in a structured manner instead of relying on bottom-up piloting and waiting for agility at scale to emerge.

- Go beyond agile teams to build connective tissue. In the scope of your transformation, rewire the entire operating model (strategy, structure, process, people, and tech) to make sure it supports and connects rather than holds back the team.

- Maintain a high speed and use front-runners. Complete the main phase of the agile transformation in less than 18 months to preserve momentum and avoid exhausting the organization; go even faster in selected front-runner areas to demonstrate commitment and early results.

Done right, agility enables a step change in performance and puts you in a position to surpass even born-agile organizations

Highly successful agile transformations delivered significant performance improvement

The essence of an agile transformation is reimagining the organization as a network of high-performing teams, supported by an effective, stable backbone of strategy, structure, processes, people, and technology. Imagine working on such a team—having the right people working together, all with different capabilities, enables organizations to move with unprecedented speed. This can increase customer satisfaction and boost operational performance. It can also provide a safe place to experiment with the authority and funds to do so, helping organizations drive more innovation. Employees will feel more engaged and enthused by a clear and common purpose, the autonomy to make decisions, and an ability to develop mastery in their craft. On the organization level, agile emphasizes prioritization and reduces overhead roles, which leads to more efficiency.

All well enough in theory—but does it work in practice? Pioneers in the field have proved that significant impact is possible, and we have documented many such examples. With this research we wanted to provide hard facts, so we asked each organization that underwent a transformation about the quantifiable improvements they achieved. Exhibit 1 shows that highly successful agile transformations achieved a step change in performance and greater impact across multiple dimensions than the less successful transformations (see sidebar “Defining success” for details on the methodology used).

What does a highly successful transformation look like in practice?

Consider Spark, an incumbent telecom operator in New Zealand that completed the first phase of its agile transformation in 2018. The operator sought to raise customer centricity, employee engagement, and speed while improving efficiency. The company cut customer complaints by 30 to 40 percent, reached a market-leading customer Net Promoter Score (NPS), received an employee NPS score in excess of 70, and launched new services faster. This led to an increased market share and sector-leading returns. The company now operates more like a digital services provider than a traditional telecom.

We find similar stories across sectors, from slower organizations starting to work with the speed of a born agile to digital native organizations to successful organizations moving up a gear. These gains in speed, customer centricity, operations, innovation, employee engagement, and productivity manifest themselves on the bottom line: 65 percent of highly successful transformations reported they had also achieved significant impact on their financial performance.

Some think that focusing on one issue naturally comes at the expense of others, for example, restructuring to cut costs (customers will suffer) or focusing on employee engagement (at the expense of efficiency). Agile transformations are different because the improvement of one dimension reinforces the improvement of another dimension: the highly successful transformations we studied showed impact across four dimensions on average.

Highly successful agile transformations also led to a three times higher chance of being a top-quartile performer among peers

Our research further showed that a highly successful agile transformation manifests itself directly by measures such as operating-model maturity and performance against peers.

To measure the maturity of each organization’s operating model in terms of agile working, we devised a calibrated scale for the different sub-elements of the five trademarks of agility—in total, 17 dimensions across the strategy, structure, process, people, and technology elements. For each dimension we used our earlier findings and casework to define a scale for what gaps, good, and great looks like. We asked all 2,190 respondents to self-rate how they experience their organization against the grid, then compared averages depending on where their organization was on its journey (see sidebar “Measuring operating-model maturity” for details on the methodology used).

As shown in Exhibit 2, highly successful transformations reported significantly higher operating-model maturity (scoring on average 3.8 out of 5, where 5 is “great”) compared with those that had not undergone a transformation (scoring 2.5 on average), or those 580 organizations that had done a less successful transformation (scoring 3.2 on average). This was, of course, expected. What was surprising, however, is that the highly successful transformation also scored higher than those that classified themselves as born agile (scoring 3.6 on average). This is highly encouraging because it means that a highly successful transformation allows an organization to overtake born-agile organizations by measures such as operating-model maturity. For example, when it comes to architecture and infrastructure, those organizations that had completed a highly successful transformation believed that their technology setup placed them at a competitive advantage, while many of the born-agile organizations, with decades of legacy in their IT setup, had to make conscious efforts to stay ahead.

Next, we studied the link between completing an agile transformation and achieving a competitive advantage. To judge performance, we asked the respondents to assess how their own organization was doing compared to their peers across financial results, customer satisfaction, speed, operational performance, employee engagement, and innovation. What we discovered was that 57 percent of those that had completed a highly successful agile transformation were in the top quartile of performance—a nearly three times higher likelihood than for those organizations that had not yet transformed (Exhibit 3).

Enterprise agility enabled those who succeeded to make their operating model a competitive advantage, with one caveat: for every highly successful transformation there were two others that missed the opportunity. Despite good intentions, high hopes, and considerable efforts, the less successful transformations achieved only incremental impact (for example, 10 percent improvement in customer satisfaction) and did not materially tilt their likelihood of being a top-quartile performer.

We next turned to the question of what sets the highly successful apart: How does an organization increase its chances of success?

A four-step recipe for success

There is a lot of anecdotal, often contradictory advice on how to succeed with an agile transformation. To separate fact from bias, we compared the highly successful agile transformations with the less successful ones to figure out what they had done differently across more than 60 transformation actions and decisions (see more details in the sidebar “Distilling the recipe that leads to success”). Putting it all together into one logistics regression model, we identified a four-part recipe that, when followed correctly, raises the chances of success from 30 percent to 75 percent (Exhibit 4).

What do those driving highly successful agile transformations do, and what should you do?

- Ensure the top team is ready to take your chance of success to 15 percent. Before launch, ensure the top team has a deep understanding of what agility is, and what it is not. This is important for getting profound buy-in from the entire top team and prepares them to lead the change. A deep understanding can be achieved in several practical ways, such as by visiting other organizations, talking to peers about agile working, and understanding enterprise-level concepts (such as the Quarterly Business Review) by doing simulations.

- Be intentional and go after value to give yourself an additional 25 percent boost. This means making a concerted, delegated, and sustained effort from the top—and clarifying how the organization creates value, where and how agile could help (for example, to enable working across functions), and then capturing the opportunities. There are many ways to be intentional: some organizations go all-in; others run the transformation in waves; larger organizations tend to train their leaders in different business units to run localized transformations. In all cases, senior leaders must role-model behaviors and mindset changes and dedicate sufficient time to the transformation. Our research clearly shows that following an unstructured, overly explorative, and bottom-up approach without a clear direction and leadership commitment hurts the chances of success. You cannot pilot your way to scaled agility; an overall enthusiasm for agile seldom translates into scalable impact without decisive leadership and action from the top.

- Go beyond agile teams and build the connective tissue by driving change across all five elements of your operating model to add an extra 15 percent boost to your chances of success. Enterprise-wide agility is more than just more agile teams—it requires changes to the entire operating model to turbocharge the teams and bring all parts of the new setup together to reinforce one another. Unfortunately, many attempt piecemeal changes when rewiring their operating model, for example, by focusing mainly on ways of working, changing the reporting structure, or adopting new technology. But what sets the most successful apart is that they view their operating model as a system and rewire all of its parts—strategy, structure, process, people, and technology.

- Maintain high speed and use front-runners to unlock the final 20 percent boost. Highly successful transformations tend to complete the main phase2 in less than 18 months. For larger organizations, the journey might consist of multiple stages, each covering a specific part of the business (for example, a single country or business unit), each executed in less than 18 months. Those taking much longer tank their chances of success. Additionally, successful transformations tend to launch front-runners early, for example, moving the first 100 people to agile teams early in the transformation to signal commitment and to start the learning that informs iterative improvement.

A detailed description of each of the four elements and their stand-alone impact on chances of success is shown in Exhibit 5. Following this recipe brings you to a 75 percent chance of success; in practice, your success will also depend on company-specific unique factors, context, quality of execution, and even a bit of luck.

Going beyond the numbers, what does it look like in practice to follow the recipe?

1. Ensure the top team is ready

Preparation is key to executing a successful transformation, and so is full commitment from the top team, which must be ready and thoroughly understand what agility at scale means.

One of the large retail groups operating in Oceania recently completed a two-year turnaround—during a COVID-19 lockdown, with teams working remotely—in which it delivered significant quick wins. It knew the next wave of performance gains would depend on local execution, cross-functional initiatives, and rapid testing and learning cycles; thus, the organization shifted to agile working. To prepare for the journey, the CEO engaged with peers in companies that had made similar changes. The top team visited agile companies in the Asia−Pacific region and Europe. The chief human resources officer (CHRO), chief technology officer (CTO), and CEO each worked with an executive from outside their own organization to guide and inspire them and also received monthly coaching. The top team mapped the impact of the changes, knowing they would also need to be reshaped. This preparation phase took several months; when the organization decided to shift, its leaders knew intimately what they were signing up for.

Another large telco company made the preparation phase even more intense for its top team. First, they undertook a tour (both virtual and physical) across a dozen agile companies worldwide. Then, convinced of the potential, they devoted three days to figure out what agility meant for their 7,000 employees, making note of what they referred to as the “scary stuff”:

- From managers to doers. De-layering from six to three levels meant asking hundreds of managers to become agile team members. Would all make the shift?

- New capabilities. New teams would require many performance coaches; yet only a handful existed. How do we train in-house coaches?

- New people model. Evaluating roles by hierarchy would become obsolete. How do we to introduce new contracts, career models, and incentives?

- Let go of (the illusion) of control. Heavy planning and reporting would not suit the new, nimble setup. How do we balance autonomy with alignment and steering?

-

Impact on us. What is our role? What do we need to learn? What must we unlearn?

After the three days the team made the jump. There was no plan B, so they set out together to solve the scary stuff.

This preparation stage should be as practical as possible. Visits to other companies, talks with peers, and case examples shared by experts help explain what agile working means at the enterprise level. Equally important are immersive simulations and leadership exercises that allow a top team to experience what enterprise agility asks from them as individuals leading in the new operating model.

2. Be intentional and go after value

By intentional, we mean that the transformation should be bold, deliberate, and executed as a coordinated, concerted, and consistent effort. It does not mean ivory-tower command-and-control style. The top team needs to be clear on where the value is and mobilize the entire organization to pursue it in a planned way.

Consider an oil and gas major undergoing a yearlong experiment with agility in its upstream organization. The journey started bottom-up, with hundreds of cross-functional teams across the business coming together to crack issues. The business value this unlocked and the positive employee feedback from the teams whet the company’s appetite, but scaling up would not be successful by simply doing more of the same: rather, the next stage needed to be intentional. After thorough preparations, the top team did three things. First, they delved into value creation, identifying the core end-to-end value chains in the organization, and determining the opportunities for simplification, agility, centralization, and digitization. They would form new teams around these value-creation opportunities, not based on functional boundaries or where people were most eager to try new things. Second, they articulated what it would take to be successful in the new environment: productivity and cost-effectiveness, flexibility to shift resources quickly to evolving priorities, and attracting different kinds of talent—and made sure all actions supported these goals. Third, they made a plan for scale-up: a front-runner in production operations, the part of the organization that required most integration and most immediately impacted value while, in parallel, kicking off the transformation at scale in all other value chains, engaging over 7,000 people across their global portfolio.

Some larger organizations drive top-down change through senior leaders. For example, Roche, a biotechnology company with 94,000 employees in more than 100 countries, launched its change efforts through a personal change program for its senior leaders. More than 1,000 leaders took a four-day immersive program that introduced them to the mindsets and capabilities needed to lead an agile organization. The intent of the program was to help leaders recognize the ways in which their individual mindsets, thoughts, and feelings manifested in the organizations they led and how to drive agility within their domain. Today, agility has been embraced and widely deployed within Roche in many forms and across many of its organizations, engaging tens of thousands of people in applying agile mindsets and ways of working.

The intentional approaches taken by these organizations and in other highly successful agile transformations contrast with those seen in many less successful transformations. In purely bottom-up transformations, there is a proliferation of good pilots and experiments, which typically run into systemic barriers (for example, culture, funding mechanisms, incentives, structures, or something else) that prevent scaling beyond the embryonic stage. As a result, benefits will fail to materialize, leaving cynics to dismiss the whole concept as a fad.

3. Go beyond agile teams and build the connective tissue

As more agile teams are launched, the structures and support around them also need to be rewired—and it needs to be done comprehensively. The operating model is a system, and if we change just one element without addressing the others, we will cripple it. Organizations must therefore pay constant attention to the strategy, structure, processes, people, and technology dimensions of the operating model. Those organizations that change only one part (for example, introduce new technology or launch culture initiatives) often encounter friction between the old ways and the new.

In 2019, Denmark’s 140-year-old incumbent teleoperator, TDC, decided to change course. It separated the network part of the business from the commercial operations and launched the strategy of transforming the latter into a digital service provider able to stand on its own feet. This 4,400-employee unit already had hundreds of people working successfully in agile teams for the digital part of the business, and scaling agility beyond teams to the entire business would best help it thrive in the new competitive arena. The company launched the “Good Rebellion”—a determinedly “go all in” change effort that resulted in clear improvements in customer results, employee engagement, and effectiveness.

In addition to defining new focus areas, such as TV and entertainment, changes in the organization’s strategy went deeper: it defined a new purpose, overhauled the entire identity, and rebranded itself as Nuuday. It changed its structure: a hierarchy gave way to flatter structure of three layers consisting of a top team, 30 unit leaders, and over 200 cross-functional teams. Reporting took place through chapters; chapters focused on consistent and scalable capabilities; and the best talent was deployed to business opportunities instead of internal coordination roles. To ensure alignment among teams, Nuuday introduced a quarterly prioritization and resourcing process, as well as a biweekly rhythm for teams to follow. To help teams continuously improve their performance and maturity, 40 agile coaches were hired (largely internally) and trained.

Nuuday made the people elements—culture, talent, leadership, and career models—a priority. It started by involving hundreds of people across the business to define the behaviors expected from everyone (for example, challenge the status quo). A new career model rewarding craftsmanship and contribution instead of hierarchical roles were also introduced, and dozens of training and communication events for the different roles and teams ensured a smooth transition. The technology setup was overhauled to allow distributed parallel development across hundreds of teams.

Vital for Nuuday, and for others driving a transformation, is a consistent new operating model—one that goes beyond team-level changes to also cover the connective tissue between them. It is especially important to address the deeper changes head-on. What changes to culture are needed to truly get the benefit of working in teams? What is the new role for leaders in an agile organization? Do we have the right people on board, or are there some we must say farewell to? By going below the surface-level changes, organizations can stay focused on being agile instead of just doing agile (see sidebar “No silver bullet, but some duds”).

4. Maintain high speed and use front-runners

While change needs to be comprehensive, it also needs to be fast (taking more than 18 months reduces the chance of success). When it comes to speed, ING in the Netherlands is a good example: it set its aspirations in late 2014, and eight months later had already transitioned its entire head office to the new ways of working. Similarly, Spark New Zealand decided that the risks of going slow outweighed those of going too fast, and opted for “giving it a big run.” Spark launched its first front-runner units within two months and the new agile organization five months later.

Highly successful transformations also use front-runners to get a head start in parts of their organization. Front-runners are not simple pilots (“let’s test if agility works”); rather, they are intentional efforts to see the full new operating model in action in a specific area—covering both agile team-level changes and the connective-tissue changes (with a scope of, for example, the first five through 20 out of 200 agile teams). This is done in an agile spirit by experimenting and iterating to make it a success, with an intention to show commitment, secure early wins, and create a starting point for the broader operating model.

One Asian telco decided to move fast. One week after a diagnostic that revealed the operating model was failing to capture $200-plus million (run rate), the top team announced the need to change. Five weeks later, four front-runner teams were trained and launched in an agile microcosmos. These teams brought together the doers across departments and tasked them with joint business objectives (for example, reducing the number of inbound service calls) rather than project milestones. Eight weeks later, the entire digital domain was transformed. These first 20 teams acted as a beacon showing what agility looked like and what benefits it could deliver.

A global iconic apparel and footwear company used front-runners when driving agility in its supply chain and logistics-operations unit. Shortly after deciding to adopt agility at scale, it launched the first agile unit of about 100 people. The front-runners were tasked with four objectives:

- discern how to get started at a high pace

- discern how to learn what to do and what to adjust before scaling further

- develop a proof of concept and demonstration of the impact of agility (even in the logistics domain)

- develop a way for people to experience what the future would look like

The decision to launch early front-runners paid off; it strengthened the “why” of the transformation and facilitated the support from the rest of the organization to succeed with the full-scale transformation.

Less successful transformations tend to spend more time and generate less impact. Agility might be a theme in year one, an imperative in year two, part of a few pilots in year three, and so on. Without momentum or examples, employees could not see how the changes affected them in practice, and they did not learn what they should do differently. Prolonged uncertainty about what agile working means to individuals (“Does all the noise about flat organizations and empowerment mean I could lose my job as a manager?”) and lack of observable changes can cause more confusion than good.

Looking ahead: Make agility your advantage

A few years ago, enterprise agility transformations were the domain of a few bold pioneers that had to discover or create the path as they moved along. Now, most organizations are racing to transform to an agile operating model. It is becoming mainstream across many sectors—the big shift to enterprise agility is under way.

Depending on where your organization is on the journey, there are different insights emerging from this research.

- For those who have not started, we emphasize the importance of solid preparation. How can you get senior leaders to fully understand what agility means in practice at the enterprise level? How can you crystallize a clear and ambitious enough aspiration for agility? How can you slow down, prevent false starts, and concentrate more fully on achieving an intentional, rapid, and comprehensive transformation?

- For those who have begun, it is time to look around and see how you are doing. These findings offer a good chance to assess how likely it is that your approach will ultimately deliver significant impact. Is the transformation solidly anchored on value creation and top of mind for the top team, or is it more of a hobby? Are you moving fast enough and showing real progress through front-runner units, or are you dragging along? Are you missing parts of the recipe?

- For those who are not seeing a step change in performance, reflect on why this is the case. Did you set high enough, tangible, and time-bound performance aspirations from the start, or let things drift at their own pace? Have you made it a priority of leaders in the organization to reach and teach these aspirations, or tried to outsource the change to coaches or separate project offices? Have you made holistic change and built the connective tissue between your teams and across all dimensions of the operating model?

- For those who are near the end, and looking beyond, how can you improve? No transformation is ever fully complete. Very few organizations in our sample rated themselves as world class across all dimensions of their operating model, yet the closer they came to this rating the more likely it was that their operating model was a source of competitive advantage. Also, what works now might not work in the future, so there is a need to constantly evolve the operating model. As one executive put it, and as we have seen with some of the born-agile organizations in our sample, “stagnation is death ... you need to ensure you keep changing faster than the market or else you are quickly overtaken.”

Agility has moved from theory to practice, from an unproven approach to a proven way to drive performance and gain a competitive advantage. We hope our findings help bring some method to the madness as you are putting together a winning operating model for today and tomorrow.