Should employers limit themselves by considering only degrees when hiring? The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, a potential recession, still-rising inflation rates,1 and the Great Attrition2 have driven employers to rethink their approach to human capital and talent management.3 Namely, they’re moving beyond degrees and job titles to focus more on the skills a job requires and that a candidate possesses. And they’re doing so in greater numbers, based on McKinsey research conducted in partnership with the Rework America Alliance, a collective that helps millions of workers from lower-wage roles move into positions that offer higher wages, more economic mobility, and better resilience to automation.4

As a pro bono contribution to the alliance, we worked in tandem to assess opportunities and actual skills-based job progressions that workers have made. Using these data, the team launched a series of practical tools, including a job progression tool5 that career coaches at community organizations such as UnidosUS, the National Urban League, and Goodwill Industries International use to help unemployed workers obtain better job prospects for the future. Our real-life experiences, along with recent research by McKinsey colleagues and others, offer lessons for what it takes to deploy a skills-based approach. From sourcing new, nontraditional talent to creating better training programs for long-term professional development, this approach is key for helping employers build and sustain a more inclusive workforce.

A skills-based approach helps both employers and workers

More employers are starting to embrace skills-based hiring practices. Large companies, such as Boeing, Walmart, and IBM have signed on to the Rework America Alliance,6 the Business Roundtable’s Multiple Pathways program,7 and the campaign to Tear the Paper Ceiling,8 pledging to implement skills-based practices. So far, they’ve removed degree requirements from certain job postings and have worked with other organizations to help workers progress from lower- to higher-wage jobs.

The interest in skills-based practices isn’t limited to the private sector. In May 2022, the state of Maryland announced it would no longer require degrees for almost 50 percent of its positions, opening thousands of jobs in healthcare, corrections, policing, skilled trades, and engineering to a bigger pool of applicants.9

Companies have recognized that skills-based practices are a powerful solution to challenges that have intensified since the pandemic. Employers have struggled to find the right candidates for important open positions and then keep the talent they hire. Through a skills-based approach, companies can boost the number and quality of applicants who apply to open positions and can assist workers to find more opportunities to advance internally, which can help employers improve retention. It also helps communities by creating more and better job opportunities for a broader, diverse pool of workers.

Attract and keep a broader pool of talent

Skills-based practices help companies find and attract a broader pool of talent filled with candidates who are better suited to fill these positions in the long term. Such practices also help open opportunities to nontraditional candidates—including people without specific or typical credentials on their résumés—as well as women and people of color.

This year, the alliance hosted a ten-week Accelerator program designed to help employers adopt skills-based practices across their talent pipeline. Participants were mostly small- and medium-sized businesses (SMBs)—along with a few larger employers—that were based in the Atlanta, Minneapolis, Denver, and Austin areas. The program consisted of four large workshops and separate one-on-one coaching sessions. During coaching sessions, participants made meaningful changes to their talent strategies to align them with skills-based practices.

These changes often generated immediate impact. Participants indicated that creating skills-based job postings resulted in a substantial increase in applications from a broader set of workers. One participant noted that making a few tweaks to their job posting quadrupled the number of applicants from two or three the previous week to 12 in the week after the new posting was shared. In the end, a successful candidate was hired when previously no applicants had passed the résumé screening.

Another participant created a skills-based version of one of their job postings and went from getting one overqualified candidate for the position to 18 appropriately qualified applicants; one was hired, and the rest were considered for other open positions in the organization.

This experience is shared by employers beyond Accelerator program participants. For example, a case study conducted by the alliance showed how a medium-sized healthcare provider created its own skills-based talent solution to address scarcity. The organization needed nursing assistants with the right skills and qualifications but weren’t getting the right applicants. They decided to train from the ground up, with two key changes: they removed role experience requirements from job postings, and they partnered with a local technical college to create an end-to-end clinical-training program. As a result, 200 new nursing assistants underwent this clinical training.

Improve internal value propositions

Skills-based hiring creates a more resilient workforce and can be an effective strategy for employers to prevent attrition, which is especially relevant in the COVID-19 era.10 Hiring for skills is five times more predictive of job performance than hiring for education and more than two times more predictive than hiring for work experience.11 Workers without degrees also tend to stay in their jobs 34 percent longer than workers with degrees.12 Therefore, skills-based practices allow employers to not only find the best workers but also retain them during a time when it is historically difficult to do so. The approach saves time, energy, and resources while fostering a more diverse and better-prepared workforce.

Build a better-equipped workforce

Last year, we shared how workers without degrees have proved they have the skills to access higher-wage, growing jobs. In the face of a potential recession, skills-based practices provide a road map for workers to make advancements internally, allowing employees to progress within their current companies during a time when external hiring could slow down. In fact, there is an untapped opportunity for internal skills-based job progressions for workers. Many employers do not have robust structures in place for workers to advance positions, regardless of their background.

A 2018 survey by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) found that 77 percent of employees who left their jobs could have been retained, with a substantial portion citing a lack of career development opportunities as a “difference maker” in their decision to leave.13 And as shared in our recent report on human capital at work, more than 80 percent of workers’ moves to new roles involve shifting from one employer to another, suggesting the workers have the skills to advance but have not been given the opportunity to do so internally.14

Creating skills-based pathways for these workers can make employers more resilient in the face of a recession while affording better, more secure employment for their workers. This approach allows for employers to create deliberate pathways based on the skills an employee already has and bridge the skills gap to the next role. Employers can proactively prepare for that progression: if employers know which skills are needed for each role in their organization, they can identify the skills gaps and overlaps between lower-level and higher-level positions and create training and transition plans to help workers progress internally.

Employers in the Accelerator program signaled their openness and excitement for creating these upward pathways for workers. The methodology they learned during the sessions helped them visualize how to make these progressions happen systematically using skills-based practices, as well as how to prepare workers accordingly (see sidebar, “Climbing a skills-based ladder”).

Overcoming barriers to implementing skills-based practices

Despite the promise of skills-based practices, roadblocks have prevented them from being more widely adopted. Some employers may understand how to implement “quick wins” but feel less certain about how to apply the practices widely or sustainably. At the same time, workers (particularly those with lower incomes) might struggle to access the support necessary to acquire jobs in new industries that require some additional training.

For employers

Many employers have found it difficult to implement skills-based practices across the whole talent journey beyond the initial stages; doing this right is about more than removing college degrees from job requirements.

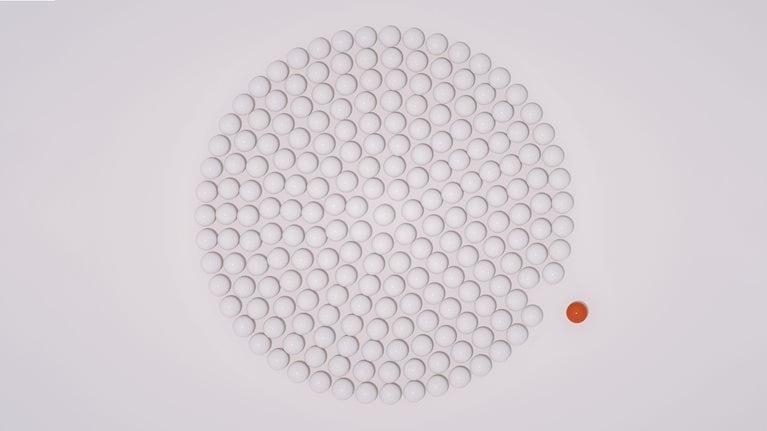

We conducted a survey in advance of launching the Employer Accelerator program, in which participants cited sourcing, validating skills, and scaling skills-based practices across the organization as three of the most common challenges they faced when implementing a skills-based approach. These results echoed what we heard in our survey of nearly 300 SMBs conducted in late 2021, in which respondents cited sourcing and validation as the top two hiring and talent challenges their companies faced (Exhibit 1).15

Employers felt unsure of how to determine which jobs—particularly lower-wage positions that many workers without degrees have—could produce the best candidates and how to communicate the opportunities available at their organizations to these workers. Though they were confident in their ability to remove degree requirements, they lacked confidence in devising appropriate and effective mechanisms for validating a candidate’s proficiency in certain skills through interview questions or assessments. These challenges are also reflected in responses to our State of Hiring Survey (Exhibit 2).

Along with sourcing and skills validation, rolling out skills-based practices beyond immediate HR professionals can be difficult: while recruiters and HR staff are often invested in skills-based hiring, hiring managers can take more convincing.

The Accelerator training program participants cited internal education and consensus building as a top challenge to implementing skills-based hiring. For example, HR managers who participated in the program noted that when they suggested removing years of experience as a requirement for a previous role and replacing them with key required skills, the hiring manager for that role questioned whether the skills could be gained any other way apart from tenure in that specific role. Others noted that hiring managers questioned producing interview guides that remove “get to know you” questions or questions about a candidate’s background—which could introduce bias—to focus exclusively on questions about historical or hypothetical demonstrations of skills, which more accurately reflect how a candidate will perform in the job.

For workers

Worker-serving organizations—community organizations focused on preparing and supporting the local workforce—note that having visible skills-based pathways is helpful in their work as they assist workers in their communities through interventions such as job coaching and career development; many use a job progression tool16 to visualize that. But common barriers still prevent workers from traversing those pathways to higher-wage work.

Bridging the gap between workers’ existing skills and the skills required to grow is challenging. While many workers from origin roles come in with strong foundational skills, such as customer service, they still require training to grasp occupation-specific skills—and there is no quick way to teach those to workers. As noted in our recent report on human capital, having six to 12 months of thoughtfully curated onboarding and coaching is also critical to workers developing and honing the skills needed to be successful in their new roles, but not many employers have implemented these structures.17

Skill and credential barriers can deter qualified workers from seeking out higher-wage positions. Twenty-six percent of respondents in McKinsey’s 2022 American Opportunity Survey cited the need for more or different experience, relevant skills, credentials, or education as the most significant barrier to seeking employment elsewhere.18 As noted in a recent McKinsey Global Survey, 87 percent of executives say they face a skills gap in the workplace, adding that recent college graduates, a traditionally reliable source of talent, often lack the required competency level for key skills.19

Tech is driving the future of the workforce in many ways, and tech skills are in the highest demand for the fastest-growing jobs. The World Economic Forum predicts that 50 percent of all employees will need to reskill by 2025 to respond to advances in technology.20 However, many workers (and particularly those with lower incomes) lack the technology-based tools that are essential to access in-demand jobs and the training that prepares workers for them. The American Opportunity Survey found that 43 percent of lower-income Americans don’t have access to broadband, 41 percent don’t have access to a laptop or computer, and 24 percent don’t have access to a smartphone. Moreover, 39 percent cite the inability to access reliable broadband as a significant barrier to doing their work.

Making a skills-based approach reality

Employers, stakeholders, and worker-serving organizations can take two strategic actions to implement basic skills-based practices and enable skills-based progressions for workers.

Get aligned and get moving

Employers can begin by aligning internally on implementing skills-based practices and ensuring that internal legal risks or roadblocks have been addressed, such as planning for the impact of removing degree requirements for workers holding H1-B visas.21 For larger companies, business units could be brought into the fold because they have power over hiring and are best positioned to determine which skills are necessary for a job.

Employers could get ahead on implementing skills-based practices by starting with quick wins, such as expanding sourcing pools or removing degree requirements from job postings. But they should keep an eye on a long-term plan: the impact of skills-based practices is maximized when they’re implemented across the whole talent journey, including in sourcing, hiring, and career development.

Sourcing. Skills-based practices can help employers draw from a wider pool of qualified candidates by focusing on the skills a candidate has more than their credentials and using inclusive language in job postings. Employers can first create a robust skills framework for all positions by defining the required skills rather than preferred competencies, changing norms to shift away use of credentials as a proxy for skills, and connecting with community organizations that provide workforce support to reach potential candidates.

Hiring. Skills-based practices can help employers ensure new hires have the skills to succeed on day one by using objective methods for interviewing and assessing candidates. Such methods focus on vetting candidates based on skills rather than more subjective (and biased) measures such as “cultural fit.” Instead, hiring managers could ask behavioral and situational interview questions that surface examples of how a candidate has or would demonstrate a given skill; build standardized rubrics for scoring candidate responses, as opposed to relying on the interviewer’s subjective judgment of the responses; and use prescreening assessments (such as work samples) that are based on specific skills rather than credentials that may or may not reflect a candidate’s ability to perform the activities of the job.

Career development. Skills-based practices can help employers upskill workers and provide learning opportunities to enable internal mobility and boost retention. Employers can design customized onboarding programs (adapting existing programs where possible) to meet new hires where they are and ensure they have the skills to succeed in the long term, provide on-the-job training and continuous-learning programs, and develop internal road maps to promotion from entry-level roles without requiring a degree.

Engage the whole ecosystem and build networks

Employers and workers themselves can do only so much to make skills-based transitions possible. The workforce development ecosystem—employers, worker-serving organizations, employer intermediaries, and elected officials—can be incentivized to work together in community to support skills-based job transitions. Support already exists: the American Rescue Plan, for example, recently committed more than $40 billion in funds to strengthen and expand the workforce. Money will go toward building collaborative training programs between public and private partners in communities across the United States.22

Leaders in each community can convene key stakeholders to support skills-based hiring and discuss how stakeholders can cooperate to ensure that workers are able to transition into higher-wage, in-demand roles in the community. Actions can include prioritizing training programs focused on the skills most frequently needed to prepare workers for in-demand jobs at local employers; sharing résumés from workers in the community who are a match for open jobs at local employers; and prioritizing investments in digital-literacy trainings and broadband infrastructure improvements for lower-income workers.

Chambers, worker-serving organizations, and employer intermediaries can also consider hosting an Employer Accelerator program to encourage local employers to adopt skills-based practices. One city government office, Denver Economic Development Opportunity, is running a program with a cohort of employers that will provide trainings, webinars, and practice events with hands-on support for employers who have additional questions. In Georgia, the Metro Atlanta Chamber is using this skills-based approach as it works with local employers to help them identify a common set of skills that are needed in certain industries or roles and equip employees with those skills. In both cases, the organizations are taking the lead in convening local workforce stakeholders and providing them with support and resources to implement skills-based practices across their talent pipeline. This leadership helps connect communities with the right stakeholders and prioritize skills-based practices among employers.

Worker-serving organizations can play a critical role by helping employers understand the nontraditional talent pools that exist in their communities and the skills they bring to the table, as well as how to address existing skills gaps. Often, however, employers aren’t connected to—or even aware of—the worker-serving organizations in their community, and they are therefore unaware of the resources those organizations offer. Worker-serving organizations and employers who participated in the Employer Accelerator program noted that simply being introduced to each other and having time to talk was critical to forming a mutually beneficial partnership. From there, they can work together to share talent sources and trainings to address broader workforce issues in their community, rather than working alone.

Chambers and workforce development organizations can make these introductions, but worker-serving organizations can also engage employers through skills-based programming that is tailored to employer needs. For example, in Austin, Texas, Workforce Solutions Capital Area partnered with tech employers to pinpoint hiring challenges and fill skills gaps. They then found trainings for nontraditional candidates, allowing the employers to reach new talent who have the skills they need while saving time and internal resources. Another worker-serving organization, Mi Casa Resource Center, based in Denver, Colorado, expanded its financial-services pathway to include HR professionals and medical administrative assistants after analysis provided by the alliance showed growth in those occupations in their community. Data from the job progressions analysis helped them develop and prioritize trainings for workers to build skills needed for these jobs, as well as make connections to growing occupations in other industries that also leverage those skills. In both circumstances, these partnerships opened new placements for workers and helped fill the talent shortage in rapidly growing sectors.

Employers are beginning to see how skills-based practices can expand their access to great talent—but the benefits aren’t only for employers. As employers adopt these practices across their talent journeys, workers are more equipped to find better jobs based on their skills rather than their degrees, educational background, or years of experience in a specific role. In the face of ongoing macroeconomic challenges, now is the time for all stakeholders in workforce development to commit resources and support to accelerating adoption of these practices and build more equitable prosperity in communities.