McKinsey for Kids: Space junk—it’s out of this world

July 13, 2022Interactive

Rockets and satellites, moonwalks and more: let’s explore space junk facts in this seventh edition of McKinsey for Kids. Find your flight suit and buckle up for a closer look at the future of space and how people are trying to deal with the stratospheric equivalent of your family’s junk drawer.

Ready for liftoff?

Ever been to a space camp, built a model rocket, or dreamed about becoming an astronaut? You’re not alone; we have been fascinated by space for as long as we’ve gazed at starry night skies.

Yet only about 600 people have ever traveled to space—fewer than might attend your local high school just this year! Now it’s getting a little easier to go to space, though.

When space exploration began more than 60 years ago, the first adventurers were satellites, not people. The word “satellite” can refer to any object in space that revolves around a bigger object. The Moon is a natural satellite because it orbits planet Earth. In this case, we’re mostly talking about artificial satellites—machines—which we first launched in the 1950s as new technologies made it possible to start learning more about space.

Did you know:

- Everyone’s heard of Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk and his giant leap for humankind. But way more satellites than people have been in space: more than 11,000 have launched in the past 60 years.

- Satellites can do a lot of things, even carry live cargo. A dog named Laika rode in the Sputnik 2 satellite in the late 1950s.

- The satellite that’s been in orbit the longest is the Vanguard 1. Launched in 1958, it continues to move through space even 60 years on!

- Which planet has the most natural satellites? Saturn, with 83 moons. Jupiter’s a close second with 80, and it also has the biggest moon—bigger than the planet Mercury!

Early expeditions paved the way for many more voyages and discoveries. They also represent the start of the “space industry,” when organizations like the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the European Space Agency were born.

McKinsey and space: Shortly after NASA was created, McKinsey was asked to help it get organized so that it could work smoothly. We worked with NASA’s Space Task Group and were involved in getting NASA’s Space Shuttle program off the ground. Our work helped NASA plan for its research and for the future.

As we mentioned, roughly 11,000 satellites have entered space since the late 1950s, and studies predict there could soon be as many as 70,000. You may wonder why we need so many satellites.

What can satellites do for the world?

A HELPING HAND

For research. The International Space Station (ISS) houses astronauts doing research on space. They might study how gravity affects your body and how objects are affected by space. This research helps us plan for future space travel and figure out how to improve problems on Earth, like exploring new medical treatments and solving pollution and climate issues.To understand weather. These satellites help meteorologists predict weather and track hurricanes on Earth.

To help farmers. Remote-sensing satellites can monitor soil conditions and check if crops are healthy. Some can give farmers clues about diseases or pests—even predicting where a destructive swarm of locusts might be headed next!

For communications. Obsessed with your phone? Communications satellites help with these connections.

Satellites can be really useful, and more of them are being sent into orbit. But here’s the problem: when a satellite finishes its work, or its batteries are exhausted, we often end up with “space junk.”

Space junk: What goes up must come down?

In science class, you might have heard the saying, “What goes up must come down.” Well, it’s not always true of satellites that are beyond our planet’s gravitational pull. With so many satellites floating around, space is getting crowded, and scientists are paying more attention to space junk.

Here are a few space junk facts. Space junk, or orbital debris, is pretty much what it sounds like: objects, or pieces of satellites and rockets, that are no longer being used but remain in space. A lot of space junk comes from old or damaged satellites or from the rocket launches that carry them into space. The debris might be as big as a rocket body that exploded (about as tall as three SUVs), but even small stuff can be a big problem.

The great junk drawer in the sky

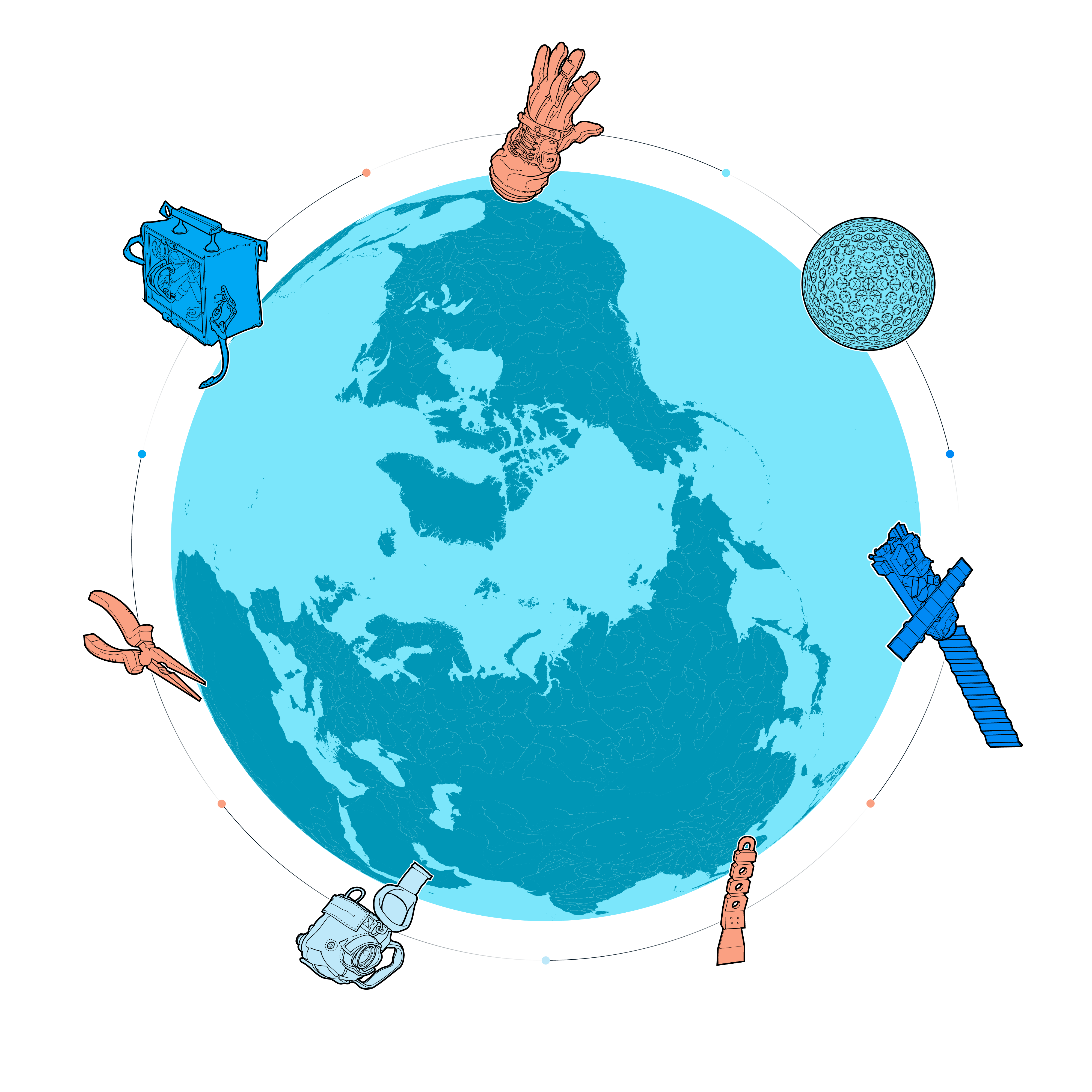

Just like the jumble of pens, paper, tools, and other odds and ends you might find lying around at home, there’s a surprising variety of space junk in the atmosphere.

SPACE TRAVELERS

Space junk has existed since the early days of space exploration. Not all items that have journeyed through space have quickly found their way back to Earth. Here’s a sampling of unique “space travelers”:1. A spare glove from 1965, misplaced by Ed White, the first American space walker

2. The LAGEOS satellite launched in 1976. It resembles a disco ball and uses laser beams to measure distance

3. The Envisat satellite, launched in 2002. Roughly the size of a school bus, it’s inactive and floating in the most crowded part of space

4. A spatula lost by Piers Sellers, a NASA astronaut and meteorologist, in 2005

5. A camera that drifted away from astronaut Sunita Williams during a 2007 spacewalk

6. A pair of pliers lost in 2007 by astronaut Scott Parazynski, after using them to repair solar panels in space

7. A 30-pound tool bag filled with grease guns and other equipment, misplaced in 2008

It might not sound like a big deal to lose a glove, but don’t forget: there’s no “lost and found” in space. Any object, even something as small as a screw, can be dangerous, since it could continue to float around indefinitely and collide with a working satellite, for example. That means there’s a big job for “space traffic controllers” to make sure that these objects don’t crash into one another.

Most space junk is in low-Earth orbit (LEO), the part of the sky that extends from the ground to about 1,400 miles from Earth. This is where you’d find the most active satellites. But even above LEO, satellites are still at risk of bumping into micrometeoroids (natural objects that chip off comets or asteroids). Those collisions are what make space junk so scary.

Out-of-this-world satellite stats

The European Space Agency estimates the number of space junk objects in Earth’s orbit today.

29,000

Can you imagine 29,000 objects larger than a bagel traveling at 10 km per second? At that speed, a crash into a 10 cm object would break an average satellite into pieces.

The European Space Agency estimates the number of space junk objects in Earth’s orbit today.

670,000

There are about 670,000 objects larger than a Cheerio traveling at 10 km per second. A 1 cm object could puncture the protective shields covering the International Space Station (ISS).

The European Space Agency estimates the number of space junk objects in Earth’s orbit today.

170,000,000

There are 170,000,000 objects larger than the tip of your pencil traveling at 10 km per second. A 1 mm object could destroy spacecraft subsystems—like the parts that turn on the power or control the height of the spacecraft.

The satellite that has been in orbit the longest is Vanguard 1, which launched in 1958.

~252,000

Vanguard 1 has orbited Earth roughly 252,000 times since 1958. This satellite is very small though, only weighing 1.5 kg, about the size of a sandwich maker.

Most space junk is quite close to us still, in low-Earth orbit (LEO).

~2,000

Approximately 2,000 km above your head is the area where LEO begins. More than 3,000 active and inactive satellites are in LEO.

Since space travel began, not too many people have made space voyages.

~600

About 600 people have orbited the Earth since the first human journeyed to space in 1961.

The International Space Station has had to move to avoid debris.

~30

Since 1999, the ISS has moved roughly 30 times to avoid approaching space junk.

1 of 7

Small objects, big problems

Earlier this year, a rocket stage, or the part of the rocket that carries fuel, bumped into the Moon. The rocket was destroyed because of the speed and the force of the crash.

Of the millions of bits of floating space junk, some are large pieces of metal, but most are only around four inches—or slightly wider than a credit card! Even something as little as a fleck of paint from a rocket’s body can wreak havoc because of its speed, thickness, or location. The fact that these objects are constantly moving makes them more unsafe.

And the space junk closest to Earth travels at more than 15,600 miles per hour. Imagine zooming around 300 times faster than your average car ride! Things moving that fast create a lot of momentum, making for a far worse crash.

As of 2022, the space junk currently orbiting Earth weighs roughly 9,000 metric tons or 20,000 pounds! Here are the largest explosions of space junk by decade:

1960s

~1,000 objects

In 1965, the explosion of satellites OV-2-I and LCS-2 created 473 particles of space junk.1970s

~4,000 objects

The 1970 explosion of the Nimbus 4 rocket body was the worst of the decade. The explosion led to nearly 400 pieces of new space junk.1980s

~6,000 objects

The accidental explosion of the SPOT I rocket body yielded close to 500 space junk pieces in 1986.1990s

~8,000 objects

In 1996, the STEP 2 rocket body exploded, and more than 700 pieces of space junk entered the stratosphere.2000s

~14,500 objects

In 2007, a satellite explosion led to over 3,000 pieces of new space junk and an enormous cloud of debris.2010s

~25,000 objects

The Microsat-R satellite was intentionally destroyed in 2019, and 400 pieces of space junk were created as a result.2020s

~31,000 objects

A 2021 missile test led to more than 1,500 pieces of new space junk floating in space.Each dot represents an object 10 cm or larger

There are a few space junk facts that might surprise you. The highest-impact collision ever recorded in space happened about 15 years ago when an inactive weather satellite was intercepted by a missile. The explosion created a cloud of space junk, with more than 3,000 objects floating in the atmosphere! In 2019, the United States Space Surveillance Network determined there were about 20,000 pieces of space junk in orbit. Today that number has grown to 27,000. Why?

There is more junk partly due to the growing number of satellites. That’s because satellites now cost less to build and launch, and some types of rockets can even be reused. And the lower costs have gotten companies, in addition to researchers, and governments, more interested in space’s potential. Now even private companies have become involved in creating satellites and in planning space travel.

All aboard for space tourism?

All that interest means the future of space could be as bright as the shiniest star in the sky. What if going to space was as easy as booking a flight to Bangkok or Paris?

NASA began space shuttle missions that took people into orbit and back to Earth from 1981 to 2011. But in the early 2000s, private companies became more involved in space travel. In the 2020s, progress started to accelerate. SpaceX sent the Crew Dragon Demo-2 into space, the first time a private company traveled to space; Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin, two other companies, made successful space flights.

Milestones in space flight

Since 2000, space tourism has become much more feasible. In 2020, private companies received almost $9 billion in investments in their space projects. Let’s take a look at the giant steps private companies have taken to explore space in the past five years.

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2017:

SpaceX completed nearly 20 space flights, reusing many of its rockets to save funds. During one of its launches, the company created a dazzling light show for those watching from the ground below.

2018:

Virgin Galactic launched its first successful human space flight. Owner Richard Branson started the space flight company nearly 20 years ago, hoping to take more people up to space.

2019:

Retired NASA astronaut Peggy Whitson, the only woman to ever hold the position of chief of NASA’s astronaut office, received the 2019 Women in Space Science Award at an event that raised thousands for science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) programs. Whitson is now commander of private space crew Axiom Mission 2.

2020:

The launch of the SpaceX Crew Dragon Demo-2 marked the first time a private company—or a company that was not connected to the government, like NASA—carried astronauts to space.

2021:

Richard Branson hopped aboard his own Virgin Galactic spaceship and headed to space. He announced lotteries to support more space travel. Nine days later, Amazon Founder Jeff Bezos flew using his space travel company, Blue Origin. He sells tickets to space that cost 20,000 times your $13 movie ticket—between $200,000 and $300,000!

2022:

In 2022, The Boeing Company, which makes aircrafts and spacecrafts, tested its CST-100 Starliner to prepare for commercial trips to space. If all goes well, the spacecraft will complete a mission later this year, maybe even piloted by astronaut Suni Williams!

Of course, these trips are still very expensive. A seat on a Virgin Galactic flight goes for $450,000, which could pay for more than 12 years of college in the US.

But in time, the lower costs of space travel could bring more people into orbit.

And as more people tour space, the problem of space junk cannot be ignored. Taking steps to keep space travelers safe is very important.

Time to take out the space trash?

If an active satellite can be destroyed by debris, how do we clean up to keep space tourists and astronauts safe?

In 2015, scientists feared the worst when they saw a piece of junk from an old military weather satellite heading toward the ISS. ISS astronauts jumped aboard a space capsule—just like getting into a lifeboat—to take them back to Earth, as a precaution. Even though disaster was avoided because the space junk passed by without making contact, future collisions are a concern. But rather than worry, we can act.

Scientists and researchers already have a couple ways of handling space junk. One idea is pretty simple: make sure that astronauts bring back whatever they originally took with them. Others involve finding better ways to track junk. For example, sensors can let observers see where and how things are moving, and alert people and businesses when the junk could be dangerous.

And in the future, new technologies might help do an even better job when it comes to a little spring cleaning in space. Many of these concepts are still being researched or experimented with. Ultimately, the goal is to nudge the space junk into a place where it could safely deorbit or be destroyed while reentering Earth’s atmosphere. A few ideas that are in the works might sound like science fiction, but they could make a big difference!

The garbage trucks of space

Harpoons

and nets

and nets

You might be familiar with these tools if you’ve ever gone fishing. Some researchers are testing whether these could also help catch bits of junk floating in space, just like the net you saw in the opening animation.

Magnets

You probably have some magnets on your fridge. Who’d have thought they could be used to catch space junk? In 2021, a special satellite with a magnetic system was launched to see whether it could snag debris.

Sling

shots

shots

Texas A&M University is whipping up something a little more sophisticated than the stick-and-rubber-band slingshot you might have toyed with when you were younger. This “space sweeper” could capture and move space junk toward Earth.

Lasers

Maybe you have a mini laser at home for playing around. Researchers are looking into using much larger, more sophisticated lasers to find debris and move it out of the way.

1 of 4

Until researchers can find a solution that works, they’ll track as much junk as they can and let people know if a collision seems likely. Alerts like these, for example, are a helpful heads up to the ISS, which has changed its orbit roughly 30 times since 1999 to avoid space junk. Researchers are also fortifying satellites to protect them from extensive damage.

How does McKinsey help with space junk?

Big problems need big, bold solutions. While organizations like NASA and academic institutions are working on it, McKinsey helps by doing research or working on smarter ways to fix space tech.

By understanding more about different kinds of space junk problems, it could be easier to create solutions that fix the biggest problems first. One type of research was to identify four basic types of junk:

Operators of active satellites can help make crashes less likely by tracking these objects and communicating with other satellite operators. They can also set up rules for getting rid of inactive satellites.

Large items (rocket bodies and dead satellites) could cause the most damage when they crash. Many space junk removal options are designed for small objects, but rope-like devices or magnets may work for large junk.

It is nearly impossible to track tiny space junk. So researchers may want to create stronger satellites that withstand crashes into this type of junk.

Operators navigate active satellites around small space junk that can be tracked. A better plan may be to look at ways of getting rid of this junk.

As you can see, there’s lots going on in space. And its potential makes for many interesting projects. Many companies are looking into how satellite information can help their efforts. Amazon, for example, started Project Kuiper, which one day could give millions of people high-speed internet through a network of satellites.

Blue Origin’s Club for the Future and other clubs like it, including clubs by NASA, the European Space Agency, and beyond, are another way young people can learn more about space or STEM subjects. This could give you a launchpad for getting more involved in space exploration when you get older.

After this spin through space, you may look at things a little differently the next time you look up. If you gaze at the night sky at just the right time, you could even spot one of the satellites launched by NASA or maybe, just maybe, an unidentified flying spatula.

Which of the following objects has ever orbited Earth?

This edition, based on reports and articles from McKinsey’s Advanced Industries Practice, comes from McKinsey Global Publishing, in a collaborative effort by Emily Adeyanju, Mike Borruso, Sean Conrad, Torea Frey, Paromita Ghosh, Eileen Hannigan, Imaya Jeffries, Richard Johnson, Stephen Landau, Janet Michaud, Kanika Punwani, and Katie Shearer, with Chris Philpot and Sinelab providing additional illustration support.

We hope you have enjoyed reading it as much as we have enjoyed making it. Do tell us what you thought of it and what else we could have done with it, or what our next McKinsey for Kids should explore. Drop a note to our publisher, Raju Narisetti, at newideas@mckinsey.com.