There are many business opportunities in Africa, but talent is a crucial component to deliver on the potential. As founder of the African Leadership Academy and the African Leadership Network, Ghana’s Fred Swaniker has long sought to support entrepreneurs on the continent. In this interview with McKinsey’s Acha Leke, Swaniker discusses what it takes to succeed in Africa and how talent and technology can catalyze change. An edited transcript of his remarks follows.

Interview transcript

Talent in abundance

I spend my life today looking for and developing Africa’s future talent. What I can tell you is that, number one, there’s an abundant source of talent in Africa. It’s the youngest population in the world; the average age of an African is 19.5 [years old], compared with 46 or 47 in Germany and Japan. And [the people are] hungry; they’re willing to learn—all they need is an opportunity.

We have been able to build a university that costs less than $2,000 a year to attend but produces graduates who are able to compete with graduates from Stanford and Harvard and Yale. They’re being hired by companies like Google and Facebook and McKinsey and Goldman Sachs, and they’re performing at world-class levels.

Companies that succeed in Africa need to look beyond the rough edges that they might see in a young African that they interview who hasn’t necessarily been to a fancy university and doesn’t speak English the way they might expect. They need to really invest in that talent, and that talent investment will reap significant rewards for them as they grow.

Technology as a game changer

Technology, I believe, is the game changer. We saw that happen with the mobile-phone revolution in Africa, where we went from less than four million phone lines on the continent to over 800 million in about 18 years. Many, many other industries are ripe for disruption and the adoption of technology—in education, for example.

We would not have been able to build this without the technology. Today, an African sitting in Kenya can get access to a world-class curriculum—can attend classes virtually from Harvard Business School, from Cambridge, from Oxford, from MIT, all in one place—because of technology.

We’re able to use technology to track the performance of students and to give them personalized feedback and education so they can chart their own learning journeys and so forth. These are all things that didn’t exist ten or 20 years ago. As such, we’ve been able to leapfrog and build the universities of the future in Africa. And, therefore, we’re able to drive significant improvements in human-capital development in a very short period of time with much less capital than was possible before.

This is really the promise that technology holds. It’s an opportunity for us to develop new business models and to adopt new practices—not necessarily best practices—because the conditions that exist in Africa require unconventional approaches, and technology allows you to redesign and reimagine new ways of doing business that can drive down costs and keep quality high.

An opportunity in every challenge

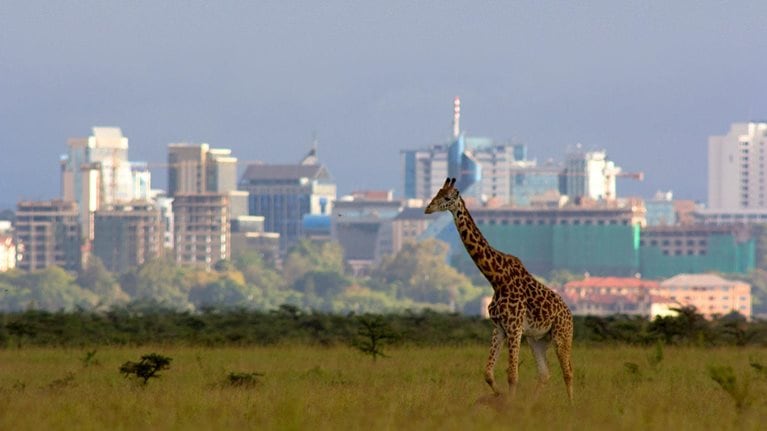

To understand the opportunities, one needs to look at the biggest challenges that Africa faces that need to be solved. These are big challenges like healthcare, urbanization, and infrastructure.

A lot of things need to be built. Eight hundred million people are supposed to move into African cities by 2050. That’s a big problem on the one hand. But it also means massive opportunities for real-estate development, urban infrastructure, urban planning, architecture, and so forth.

If you look at agriculture, and you realize that today Africa imports about $40 billion of food that Africa has perfect conditions to grow, that’s a great opportunity for someone to build an agribusiness.

Those businesses that thrive are those that realize that their role in Africa is not simply to make profit but to contribute to the development of a whole country—and eventually the whole continent. When you’re in Africa, you’re not just doing business—you’re touching lives, you’re transforming societies, and you’re really creating history.