Coca-Cola has had a presence in Africa since 1928, when the first bottle was sold in Cape Town, South Africa. But its approach has changed in the past 90 years. Liberia-born Alexander Cummings served as president of Coca-Cola’s Africa Group and later as the company’s chief administrative officer. He retired to focus on philanthropic efforts, including the Cummings Foundation, which he launched in 2015. In this interview with McKinsey’s Acha Leke, he talks through opportunities on the continent, as well as how to craft a strategy for doing business in Africa and nurture lasting relationships with local customers. An edited transcript of his remarks follows.

Interview transcript

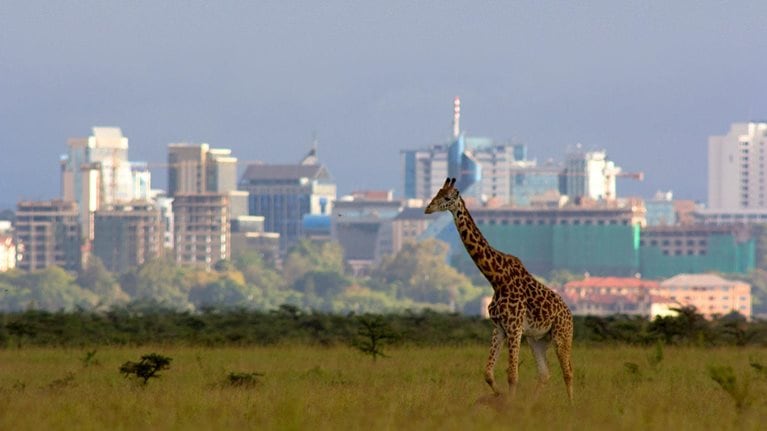

The value is here—the opportunity to be first in many categories still exists. If you have a medium- to long-term point of view, if you want to be first, if you want to build your brands, if you want to become a part of the fabric of communities around the world: Africa is the place you need to consider.

Mapping Coca-Cola’s Africa strategy

Africa is a very large continent. Most people don’t realize that you can fit three North Americas in this continent—it’s quite big, 50-plus countries.

While [Coca-Cola] wanted to have a broad presence across the continent, it was also important to us to focus and prioritize. We looked at things like per capita incomes in the countries around Africa. We looked at population; we looked at economic growth; we looked at governance in various countries. Given all that information and data, we identified something like seven or eight markets that we wanted to focus on.

In strategy and in business, [making] choices and prioritizing are where you can have the most impact. We chose to map our strategy around these key countries, these key markets, these key cities. I would encourage anybody considering coming to Africa to think along those lines, as opposed to trying to go too broad—because it’s a complex continent.

Partnering in Africa’s development

It’s important that multinationals engage government—whether it’s a ministry of finance, a ministry of trade and industry, directed territories—to make sure they understand the proposition, what your business offers, what it does.

Governments are interested in job creation, so to the extent—either directly or through your value chain, your supply chain—you can create jobs, you will typically get a very receptive ear from governments in that area, because that’s the biggest challenge.

To the extent you can provide training and development for young people in African countries, you will get a receptive ear. The triangle—working with civil society, working with government, and [working with] the private sector—is the ultimate way we will solve a lot of our challenges in Africa.

Building local relevance

I recall when we set up the 50th anniversary of Coca-Cola in Kenya. We were all sampling and handing out cold Cokes, and this young man came up to me and asked me where I was from. I said I was from Liberia, but I lived in the United States.

And he said, “So, is Coca-Cola sold in the United States as well?” It might sound unbelievable, but it is a true story. That said to us that our brands were loved, and people understood the connection and the benefits we brought.

These are stories that talk about the fact that we are local: we employ locally, we purchase locally, and we give back to communities and societies. And having the local insights—people who understand the continent, who believe in the continent, who believe in themselves, who will advocate for the continent—is something I think is important.

[You also need] to make sure that everybody along the supply chain makes a buck. Coca-Cola’s very intentional about understanding not just what we make—or just selling to the next person in supply chain—but understanding all the way to the village that everybody makes a buck, and that the product [needs to end] up being affordable. When that happens, there’s a natural incentive. Capitalism works.