As the world grapples with what some have deemed “the age of urbanization,” affordable housing has become a great concern. At a conference held in Nairobi, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) discussed what affordability means, how various countries are tackling the growing challenge, and what more can be done. Affordability, as defined by the authors of a recent MGI report on affordable housing,11.For the full McKinsey Global Institute report, see “Tackling the world’s affordable housing challenge,” October 2014. is the threshold of financial burden that an individual household will bear—about 30 percent to 40 percent of income. Three of the authors of the report, Jonathan Woetzel, Sangeeth Ram, and Jan Mischke, gathered with several housing and urban-development experts, including Dr. Joan Clos, executive director of UN-Habitat, Britt Gwinner of the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, and Kenyan housing official Jane Weru. Edited transcripts of their conversations follow.

Dr. Joan Clos: Putting housing at the center of urban strategy

In order to confront the issue, we have developed a new theme. And this new theme is housing at the center. We mean two things with that, that housing should come back to the center of the urban strategy: urban planning, design, and urban strategy.

For example, we know about central business districts, which are a common feature of many new urban projects. We know a lot about industrial-land zoning, which, for example, is one of the most common zoning of cities in China. And housing has been diluted in these urban strategies.

There’s a third paradigm in our housing policy: The first two are housing at the center of the policy, housing at the center of the city, and the third one is that, before you build affordable housing, you need an affordable plot, an urban plot, to build the house on.

A good planned city increases the productivity of the economy. They call that “economics of agglomeration.” They say that in the well-designed urban space, the factors of production are closer. When the factors of production are closer, the cost of transaction is lower.

And when the factors of production are nearer, and the transaction goes lower, the productivity goes up. And this is a very substantive increase of the productivity. This is why all the finance ministers, when they need taxes, know where to go to collect taxes—they go to the cities. Because in the cities there’s a lot of value generated by the process of urbanization.

These economies of agglomeration flourish when the urban structure is well designed. What creates urban value is the location of the buildable plots. This is the origin of urban value—the good location of the buildable plots.

Britt Gwinner: Tackling high construction costs in Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, more than many other regions of the world, the construction industry and the supply chain are inefficient and atomized. So, nowadays, in commercial, moderate-cost developments around Kenya, you see construction costs per square meter that are much higher than other parts of the world. So $700, $800 per square meter to build a unit to deliver to a moderate-income household, versus $350 in South Asia, and as low as $250 per square meter in parts of China.

And there’s really no scientific reason why it should cost that much to build houses here. It really has more to do with the depth of development and efficiency of the supply chain, the way builders work, access to large tracts of land, and the cost of infrastructure.

One of the things about this market that you see any place in the world is nobody’s responsible for the whole thing. So you always have this coordination issue. And it’s always something that has to be overcome over time. So what we’re seeing is more and more interest in this region. And it’s something that we’re trying to support.

And we’re supporting that with investments in producers of cement and steel bar to increase, to get an increased production of materials, and also to bring scale to the building process, to move away from 300 units at a time to 5,000 to 8,000 units at a time, in a given development, that allow you to profitably make the capital investment that it takes to bring in some of the industrial methods that the report talks about.

Jane Weru: Securing land to build on

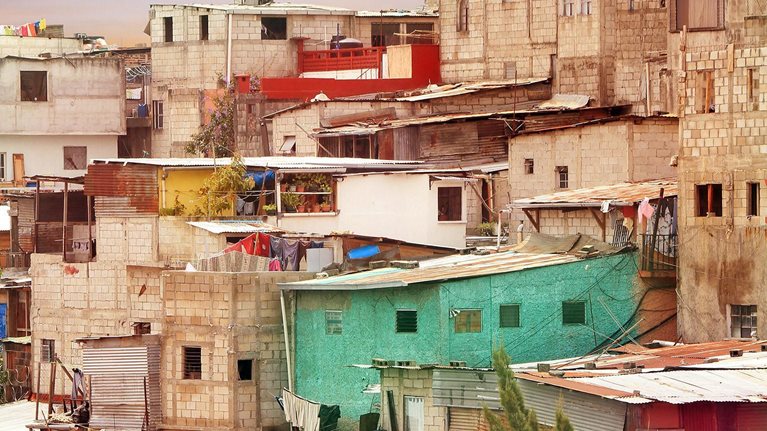

In Nairobi, like we’ve all said, one of the major challenges is land. I would say there are about 200 informal settlements. Out of those 200 informal settlements, about 100 of them are on private land. Let’s say probably more than half of them are on private land.

Probably the most challenging of these are the Mukuru slums. We look at Mukuru kwa Reuben, Mukuru kwa Njenga, near the industrial area. Here we have about 500,000 people, about 150,000 families, who live on about 450 acres.

And all these 450 acres are on privately owned land that was given in the ’80s and ’90s, was never developed by the developers, that was given to develop plight industries. They never bothered and the land was encroached upon. And now we have whole communities on it.

Would you like to learn more about the McKinsey Global Institute?

So many of the owners are now looking to sell what they initially held. Now the challenge is what do we do with these near 500,000 people? Do we let the private developers sell and cash in on a public grant that was given to them for development?

And I think this is something that governments elsewhere have taken advantage of and have recaptured the land that they had initially given, to request the Kenyan government to have the courage to make use of these contractual conditions that are in these grants, to take back land that is rightfully its land because it has not been developed, so that the land can be redeveloped for low-cost housing.