Over the past decade, many retailers have introduced “lean” techniques into the store environment. And they’ve done it for good reason: lean store operations can yield significant results—typically a 5 to 10 percent increase in sales, a 15 percent reduction in operating costs, and as much as a 30 percent decrease in inventory costs.

But most retailers, even those well acquainted with lean principles, struggle to sustain the impact of their lean-retailing efforts. According to a recent McKinsey survey of retail managers, 60 to 70 percent of store-transformation programs ultimately fail. In service operations like retail, change must be implemented by many people—as many as tens of thousands of employees. And when frontline workers have become accustomed to replenishing shelves in a particular way or when store managers have done personnel planning on their own for a decade or longer, making new behaviors stick can be extremely difficult. People tend to revert to old behaviors when they don’t fully understand either the problem or the solution, when they’re not held accountable, or when they don’t see others consistently behaving in the new ways.

As we’ve worked with leading retailers worldwide, we have identified common mistakes that retailers make in their lean-transformation efforts, as well as a set of practices that can yield significant, lasting impact. These practices, which revolve around building an inclusive core team and pulling the critical levers that influence mind-sets and behaviors, may sound simple and obvious—but, in our experience, many retailers either execute them haphazardly or overlook them entirely.

Building a core team

From the very beginning of a lean transformation, employees at every level of the workforce—from regional managers to store associates—must feel they have a voice in the project and can contribute to shaping the solutions. Employees’ early involvement helps create the conviction, momentum, and passion to effect change.

Too many retailers make the mistake of imposing solutions developed by a small, exclusive team from corporate headquarters. A better approach is to establish a core team that includes handpicked store managers, district managers, and staff from the central functions, so that every part of the organization is represented from day one. This team of high performers should remain intact for the duration of the effort.

Retail executives may object that the size of such a team would be unmanageable and would slow down decision making (as the example in Exhibit 1 shows, 16 people were on the project team in phase one). Experience has convinced us, however, that the trade-off is worth it. A larger, cross-functional team may add complexity at the start of the project, and achieving alignment may initially take longer—but these risks are a small price to pay for the cocreated solutions and organization-wide buy-in that a more inclusive team can generate.

A core team consisting of employees from both the store network and central functions can make better-informed decisions and develop realistic, pressure-tested solutions. For example, at one grocery retailer, store personnel who were on the core team suggested presorting and packaging certain products in a way that would reduce shelving time at the stores. Managers from corporate headquarters were able to weigh in during the discussion: they explained that the goods were stocked in different locations in the main warehouse and therefore couldn’t be packaged together without incurring substantial warehouse costs. The team thus came up with a different, more cost-effective solution.

At another retailer, store employees had to use three different formats of price tags, one of which required six times the handling effort of the other two. A team consisting of store employees and marketing experts was able to develop a new price-tag format that had comparable visibility but required much less handling effort—leading to a 10 percent improvement in the efficiency of the overall price-tagging process.

An additional benefit of a large core team is skill building. Store managers who become part of the core team get the opportunity to learn and hone valuable management skills such as how to run analyses, document findings, track performance, and oversee multipart projects. We often find that retailers are pleasantly surprised at the potential they discover in their store managers.

Creating lasting change

Once the core team is up and running, the hardest part begins. Among the team’s primary responsibilities should be to see to it that every individual in the organization makes the necessary changes in mind-sets and behaviors. To do this, they must pay attention to four levers: organization-wide communication of the need for change, formal mechanisms that reinforce the desired changes, a well-designed capability-building program, and role modeling (Exhibit 2).

Communicate the need for change

Most retailers already know that communication is critical to the success of an organization-wide effort. They therefore kick off their transformation programs by hosting town-hall meetings, large workshops, or road shows led by senior management; top executives champion the effort in staff meetings and in employee newsletters or internal blogs.

Such activities are important—but we’ve seen many retailers simply communicate the change, instead of the need for change. They hold pep rallies to build excitement about the change and then send out detailed technical descriptions to help employees implement the new processes. But these types of communications rarely convince the workforce that change is necessary. Why were the old ways suboptimal and how are the new ways better? Without an articulation of the need for change, a lean transformation could be dismissed by employees as a “flavor of the month” or a vain attempt by a CEO to bring about change for change’s sake.

The most successful retailers make sure to disseminate carefully constructed, persuasive messages about the pain points that the lean transformation is designed to address, the virtues of the proposed solutions, and the expected measurable impact. They craft a “change story” that every employee can relate to. One retailer’s change story centered on the company’s successful history, recent shifts in the competitive and consumer landscape that made “business as usual” a losing proposition, and the company’s responses to those shifts. The CEO told the story on day one of the transformation and company leaders repeated it constantly for the duration of the effort, linking every initiative back to it. The company used a variety of communication formats and channels—including in-person meetings, an employee-suggestion scheme, print and electronic newsletters, and posters—to reach employees regardless of their communication preferences. According to senior executives at the retailer, the change story helped create strong employee commitment to the transformation program, a sense of urgency and conviction around the need for change, and widespread support for the program’s individual measures.

Set up formal reinforcement mechanisms

To help ensure that frontline employees are executing improvement measures correctly and consistently, retailers should establish reinforcing mechanisms—including a strict certification process that assesses various dimensions: understanding (do employees understand the need for change and the new processes?), implementation (are the new processes in place and are all required tools available?), and impact (are the new processes meeting predefined targets?).

Typically, retailers’ certification programs take into account only implementation and impact—neglecting the “understanding” part, which, as discussed earlier, is crucial to surfacing implementation issues and sustaining impact. One retailer has made district managers and regional managers responsible for the certification process: they conduct store checks and in-person interviews with store employees. The interview questions are designed to probe employees on not only what the new processes are but also why they use the new processes.

In some cases, a retailer’s certification program isn’t as effective as it could be simply because it’s used only once: immediately after rollout. Store employees tend to perform well during that time, but without continued accountability, the likelihood of employees returning to old behaviors is high. Smart retailers do multiple certification rounds to reinforce the desired changes: immediately after rollout, then three months later, then again a year later.

In addition, leading retailers link employee incentives, such as pay raises and bonuses, to certification results—making it clear to all employees that there are rewards for getting certified individually and as a store staff, as well as consequences for failing to get certified or for missing targets. The core team agrees on an escalation process and personnel measures to take in the event that targets are missed.

Invest in a capability-building program

Many retailers zero in on one question during lean-retail projects: “Which operating procedures are the best for us?” Once they’ve identified those procedures, their attention level falls and they end up underinvesting in training the workforce to put those new procedures in place. In our view, the more important question is, “How can we mobilize our entire workforce to adopt the best operating procedures?”

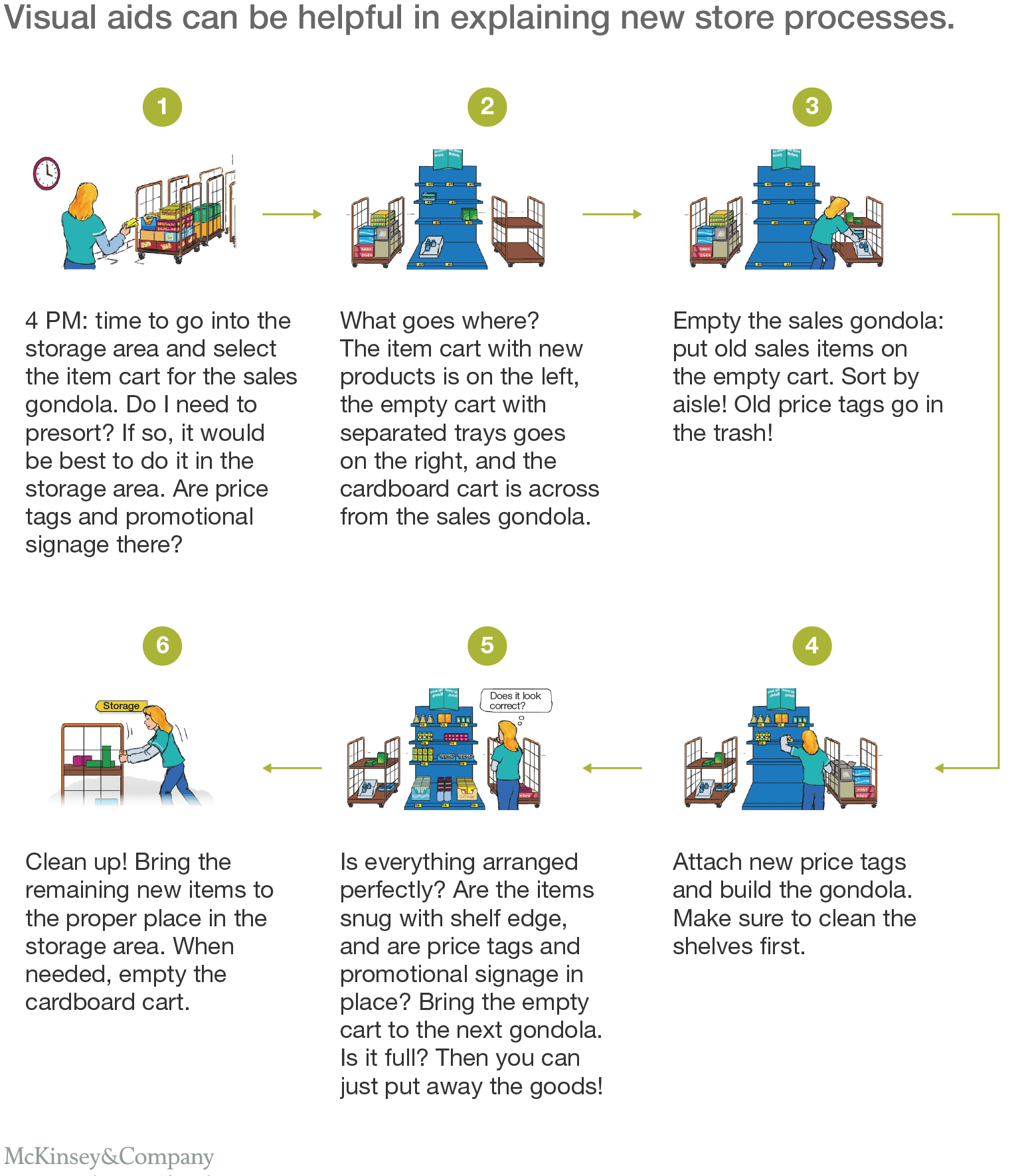

The most advanced retailers employ a blended approach to training—one that combines classroom-style learning with practical application and rigorous assessment. We’ve found that the ideal training mix is roughly 20 percent theory, 70 percent practice, and 10 percent assessment and evaluation. To train cashiers on a new checkout process, for example, 20 percent of training time could be spent explaining how the new process differs from the old one, what problems it is meant to solve, and exactly how it solves them. Some companies, to guard against the common problem of store managers feeling ill equipped to train store employees, create detailed how-to manuals and training handbooks. One retailer used colorful comic-strip illustrations to show a new shelf-stocking process (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3

The bulk of training time could then be devoted to in-store application of the new processes—for example, cashiers practicing new procedures on cash registers at checkout lines. Our experience has taught us that training store employees outside the store environment (at off-site sessions, for example) has little value. A more effective practice is to designate a handful of “training stores”—ideally, stores that are representative of the store network, conveniently located and easily accessible to most employees, and spacious enough to accommodate trainees from other stores.

Training sessions should be fairly small to allow for thorough coaching. One retailer put two “change agents”—typically members of the core transformation team—in charge of training groups of ten employees at a time, for a trainer-to-trainee ratio of one to five. Some retail executives might worry that such an approach to coaching would take too long, but again, our experience shows that the investment pays off quickly and is crucial to making the changes stick.

Additionally, assessment and evaluation are an indispensable part of a complete training program. We have seen retailers use a variety of tools—including activity boards, checklists, skill matrixes, and individual coaching plans—to help employees know where they stand and how they can improve. Some retailers use daily briefings for live problem solving, allowing employees to discuss performance and determine corrective actions. Regular check-ins among leaders of rollout teams, as well as specialized workshops to address particular issues, can also be tremendously useful.

Model the desired behavior

Role modeling, whether by higher-ups or by peers, is a powerful lever for changing mind-sets and behaviors. Store managers should consistently use the new processes and reward and recognize store employees who behave in the new ways. Regional managers and district managers should visit stores frequently, using these visits not to conduct store audits but primarily to provide coaching on the new processes. Senior executives should drop in on stores as well; their in-store presence can motivate staff and reinforce new behaviors.

Perhaps the most visible role models in a lean transformation are the change agents and coaches responsible for training the store staff. The caliber of these coaches can make or break a lean-retail program. The most successful retailers don’t compromise in this area; they select their most talented employees as coaches, even if it means temporarily taking those employees away from their day-to-day duties. And they don’t skimp on the time it takes to train the coaches.

Individuals can serve as role models, but so can entire stores or clusters of stores. For some retailers, digital and social media have been effective tools for highlighting best practices and disseminating success stories across the company. On intranets, internal blogs, or message boards, announcing the achievements of an employee, store, or region can build buzz, establish role models, and engender friendly and healthy competition.

Some of these practices may sound time-consuming, but in our experience, rolling out lean operations to a network of hundreds of stores and tens of thousands of employees can take less than two months. And with a cross-functional core team in place and deliberate attention to the most important change levers, retailers can prevent employees from falling back into old habits. Results can thus be sustainable in the long term.